Page 26 - DesMoinesRiver

P. 26

“appointed” to the role chief, and given the power to negotiate and sign trea- Black Hawk and his followers staunchly maintained their residency at

ties. This went against the traditional political structure of the Sauk and many Saukenauk.

met it with derision. Others, seeking a new way in an unfamiliar and perplex-

ing new order, chose to follow him. In 1831, following their traditional practice, the Sauk left Saukenauk for

their winter hunt. While they were gone American settlers moved onto

Ma-Ka-Tai-Me-She-Kia-Kiak , Black Hawk, was a traditional Sauk war leader, the village lands. When Black Hawk and his people returned in the

a role different from that of a civic leader. As a young man, he earned this spring, the Illinois militia was called in to drive them away. Numerous

battles followed, fought in Illinois and Wisconsin. These became known

status leading war parties and fighting on as the Black Hawk War (Green 1983:132; Peterson and Artz 2006:36).

the side of the British during the War Black Hawk was eventually defeated in 1832 during the Battle of Bad

of 1812. During this war he led attacks Axe in Wisconsin.

against American interests at Fort Madi-

son, Prairie du Chien, and elsewhere. Black Hawk was captured and held as a prisoner by the U.S. Govern-

His cause was lost with the defeat of ment. He and a number of other captive leaders were taken to a

the British at the end of the war. prison in Virginia. From there they were taken to Washington D.C. and

eventually to the prison at Fort Monroe. In 1833 they were returned

Black Hawk did not advocate coop- west via a circuitous route through a number of large cities on what

eration with U.S. Government poli- was referred to as an “escort tour.” They met President Andrew

cies. In 1804 when the U.S. Gov- Jackson, their portraits were painted, and they were given numerous

gifts. The purpose of this tour was to convince them of the power of

ernment tricked the Sauk and the American government and the inevitability of the American take-

Meskwaki into jointly signing a over of the west. During this time Black Hawk told his story to An-

treaty that ceded all of their toine LeClaire, a government interpreter who was of French-Canadian

territory east of the Missis- and Potawattamie heritage. The story was published in 1833, one of

sippi River Black Hawk the first accounts of a Native American leader’s life (Black Hawk 1994

objected (Peterson and [1833]).

Artz 2006:34). He

refused to recognize Black Hawk was freed in 1833 and allowed to return to Iowa with his

the validity of the family. He apparently established a winter lodging along Devil’s Creek

treaty, claiming in Lee County and had a summer wickiup near James Jordan’s trad-

that those who ing post in the vicinity of Iowaville (Peterson and Artz 2006:40–41). It

signed it had is known that Black Hawk was living near Jordan when he died in the

no author- autumn of 1837. He was buried near his wickiup, but the grave was

ity to do so. soon robbed of both body and artifacts. In 1843 Jordan pointed out

The Sauk the spot to the surveyor William Barrows who noted its location, but

divided over all traces of it now appear to be gone (Upp 1974:2).

the issue.

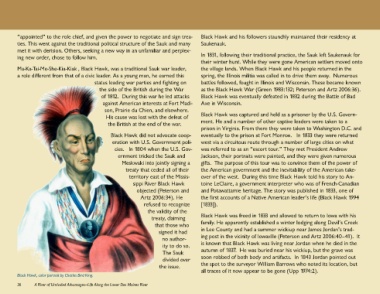

Black Hawk, color portrait by Charles Bird King.

26 A River of Unrivaled Advantages—Life Along the Lower Des Moines River